This post has been months if not years in the making. Partly, because of the complexity of the topic and partly because it seems; as hard as a try there is always something more to learn.

If my husband or I host you with frequency there is a good chance you have visited Caldwell Vineyard. Afterall; John Caldwell is indeed a legend and meeting him truly adds dimension to your wine experience. When John is not available to host you may just get lucky enough to visit Ramiro Herrera the in-house Master Cooper.

Ramiro Herrera, Master Cooper

It is about Ramiro and his craftsmanship and trade that I have been meaning to write for a long time. Ramiro has the peculiar task of fabricating the barrels used to age Caldwell wine. Barrel-making or cooperage is a centuries old art that is quickly disappearing. There was a time in which barrels made of various woods were the main means of storage for shipment as well as land storage. Historians tell us that barrels were designed to be dry for the storage of goods that were not easily damaged by humidity, Drytight for water-sensitive goods like flour or sugar and wet, which is the only barrel tradition that remains. Wet barrels, the kind utilized for the fermentation and aging of wine and spirits generally require deep artistry and technical knowledge. Cooperage is a trade learned not through schooling but rather through a rigorous process of apprenticeship. Becoming a master cooper demands a deep love for woodworking, a strong understanding of nature and a tremendous olfactory talent able to predict the potential of wood through the curing process and throughout the toasting process.

Out of professional curiosity and shared passions I have made it a point to spend time with Ramiro listening and observing. The time spent together gives me a profound appreciation for the way a barrel influences the flavor and consistency of wines. In fact, about 50% of what we recognize as flavor in a wine is not the result of the fruit, the yeast, the terroir or any other factor involved in wine making. Half of the flavors come from the barrel. Within the oak there are endless nuances that are released to perfection when a Master Cooper carefully toasts the wood. Flavors like vanilla, mocha, coffee, chocolate and coconut as well as tannic characteristics are released from the wood when exposed to carefully managed flame. By the way, the fire toasting the barrel is made exclusively from the same pieces of the oak left from shaping the staves that make up the barrel.

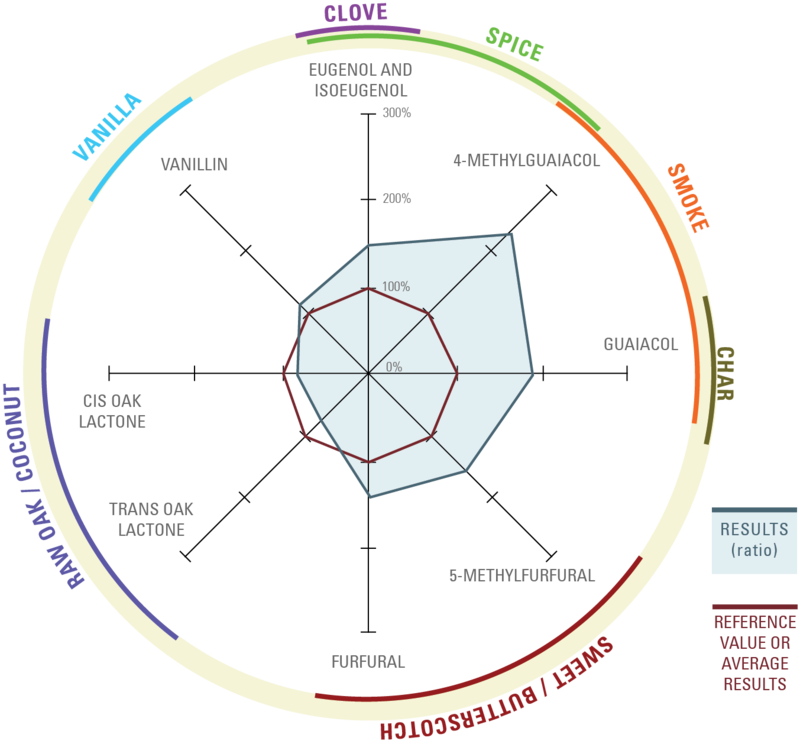

I was feeling geeky so I opened a book I received as a gift that talks about the art of barrel toasting. I decided it would be good to share with you so we can geek out together. In oak barrels you will find the following flavors:

- Oak lactones: The two main aroma constituents of raw oak, often described as fresh oak or coconut.

- Vanillin: A phenolic aldehyde resulting from lignin degradation. It is the main aroma compound of natural vanilla.

- Eugenol: Volatile phenol produced in the oxidative breakdown of lignin during air drying; possessing spicy, clove aromas.

- Guaiacol: Volatile phenols, resulting from further thermal degradation of phenolic aldehydes, with smoky aromas, char aromas, spicy characters.

- Furfural: Produced by the degradation of carbohydrates by heat during barrel toasting. These compounds possess aromas of butterscotch, light caramel, and faint almond. Barrels should be carefully selected for a specific purpose.

- Spirits/Wine: Used oak will also impart flavors of it’s previous life.

If nothing else, this list will prove useful when trying to impress your friends when you are partaking of lovely wines together.

Ramiro discovered his passion as a tonnelier while working at Seguin Moreau, his gifts and inclination for the trade did not go unnoticed and he was promptly sent to France to apprentice under the very best. His four-year apprenticeship had a cohort of forty. At the end of the training only two of the forty apprentices that had started acquired sufficient expertise to receive the title of Master Cooper. This my friends, is a personal achievement comparable with graduating from an Ivy League institution at the very top of your class!

There are endless aspects of Ramiro’s journey that mimic mine. He is a self-made man whose skills have flourished through sacrifice. He is deeply in love with his profession and is always looking for ways to improve in what is already a superior product. As the only Master Cooper of Mexican-American ethnicity he is a role model to many and a man of great generosity always willing to teach and reach out.

Making barrels is no easy feat. For starters, barrel makers engage in bidding to purchase 100+ year old logs from selected forests in France. Once logs are secured they are shipped and prepped for a 2 year curing process aimed at drying of the wood to diminish tanic characteristics as well as the absorption of microbes that will ultimately shape the flavor of the wine. This is just the beginning. Once the wood is cured the Master Cooper must carefully shape the staves in a multitude of widths to facilitate the curvature and bending of the barrel which will be shaped through the tightening of steel ropes and held by hoops which in the past were made of flexible wood known as withies but are now made through the forging of iron. The structure of the barrel must allow for expansion and contraction of the wood while remaining impermeable.

I am a curious person and always eager to learn. That means I could potentially write a book just based on all the amazing conversations and time spent in Ramiro’s workshop. Instead, and in order to give him a personal voice so you can get to know him better I decided to ask him a few questions. My hope is that you too get to know and understand the essentiality of his work in the making of consistent and flavorful wines.

How about you join me on this post so you can get to know Ramiro better as we chat with him about barrel-making

Leave a Reply